THREADSTACK Interview with Lia Pas of The Slowest Thread

"When I'm symptomatic it helps to visualize what I am feeling and "dissect" those sensations to make them less overwhelming. Freehand stitching those sensations feels like a meditation practice."

I have been mesmerized by the embroidery art of

from The Slowest Thread for since first seeing this work here on Substack and was surprised to learn that embroidery is a fairly new medium for Lia. The work she does is stunning, and it isn’t just that it looks pretty, but rather that it raises awareness and explores the lived reality of chronic illness through textile imagery. It’s powerful. It stops me in my scroll every time.So I’m thrilled to bring you this interview with Lia and hope that it will inspire you to go see more of what she does. In it, Lia shares the experience of changing mediums due to health, beginning to identify as having a disability, reading Van Gogh Blues, and so much more.

Who is Lia Pas?

I have been a multidisciplinary artist all my life. I was a composer/performer who worked with dancers before I became disabled by ME/CFS and had to change my creative practice to honour my limitations. Embroidery is a newish medium for me, but my previous work in performance and writing has greatly informed my fibre art.

When and how did you first learn to embroider? Do you have a specific memory of some of your early embroidery?

The first needlework I did was Ukrainian cross stitch in my teens. My younger sisters were in Ukrainian dancing and my mother had to make their costumes. I was already sewing many of my own clothes by this point and my mom asked me to help. We went to a workshop organized by the Ukrainian dance school and the cross stitch and patterns came very easily to me. I think I probably did most of the sewing and cross-stitch on their costumes.

My embroidery practice came when I got sick in my mid-40s. I am completely self-taught. I wasn't especially interested in the embroidery patterns I saw online—I am not a flowery person—so I started stitching some digital SciArt text/image pieces I made before becoming ill. When I started, I looked up various stitches online and used my pieces to practice them and designed a mitosis sampler for myself to learn some of the trickier stitches. (I'm currently writing a pattern of that one.) With my first piece I was hooked, and embroidering anatomy and my symptoms followed soon after.

At first I was stitching for most of the day because I needed to rest so much. My pieces got bigger and more complex very quickly because setting up a piece takes so much more energy than stitching it. As I regained some of my energy and cognitive function I started writing and making music again, but embroidery is my main restorative activity. This past year I've had a series of liver infections which has meant I've done a lot more embroidery than usual. I bring it to the hospital when I'm admitted for something to pass the time while there.

It is such powerful work. I have spoken with many people whose medium and scale changes with illness. Often, people speak of having to go to a smaller scale, so it is interesting to learn that working bigger works better but your explanation of why makes a lot of sense!

For those who know about embroidery, what might you share about the stitches/techniques/materials that you use?

The first step I take is to scan in and then size the base image so it will be large enough for the stitches I have in mind and for any text I have planned around the image. I print the image on paper and trace it onto the cloth—almost always linen, but occasionally cotton—with a DMC water soluble marker on lighter coloured fabric or a Bohin chalk pencil on darker colours. If I'm using a more complex image or I'm working on very dark-coloured cloth I'll print it on Sulky dissolvable material and stick then baste it to the cloth to stitch over. The Sulky also works great for large blocks of text.

I'll usually choose thread colours and thicknesses as part of the set up for a piece and use my DMC thread sample book if I need shades I don't have in my stash. I generally use a fairly muted palette, choosing colours either based on gross anatomy photos or on the sensations I feel.

I almost always start stitching the general outline of the base image and then the details. I usually decide on some of the stitches ahead of time but allow myself the option of changing those or the colours if they don't seem right once I get started.

After the base image and details are stitched I start working on the symptomatology lines. These are usually done completely freehand since I stitch whatever I am sensing in my body in the moment. Adding the text, if any, is the last step so it lines up nicely with the image.

My favourite stitches are chain stitch using a tambour hook with size 8 or 12 perlé thread for larger pieces since that is a much faster technique than other hand stitching. I also use a lot of whipped back stitch since it gives very clear-edged lines. I often use single strands of floss for fine details either as back stitch or whipped back stitch which works especially well for text.

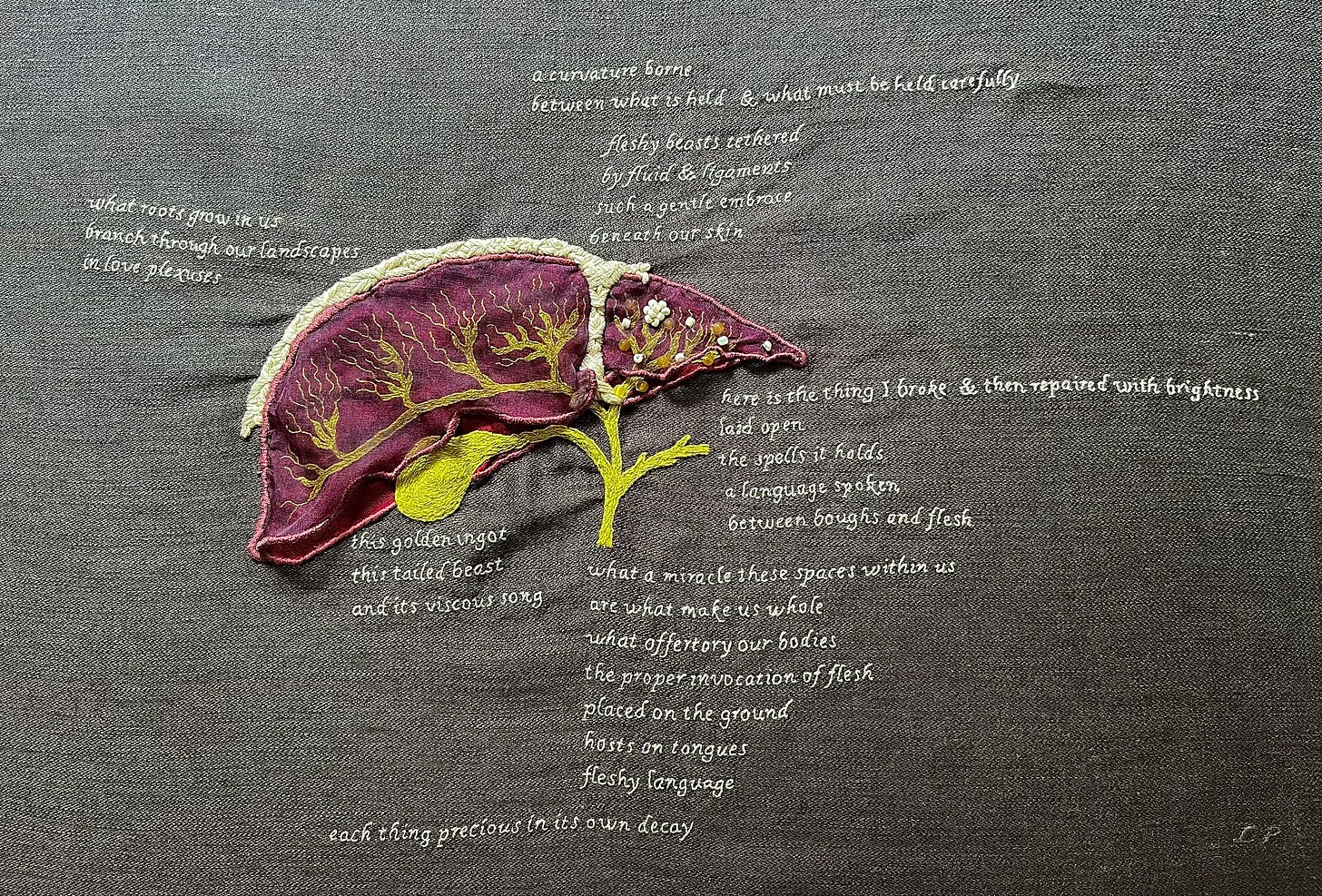

I occasionally add beads to pieces if the imagery demands it. Usually beads represent heavier symptom sensations or actual growths on the organ. I've used organza appliqué in one piece—my liver embroidery—since I wanted to show the top and bottom layers of the organ and how the biliary ducts sit within it.

You have touched on the content of some of your work. Can you tell us a little bit more about your three embroidery series: microscopy, anatomy, and symptomatology?

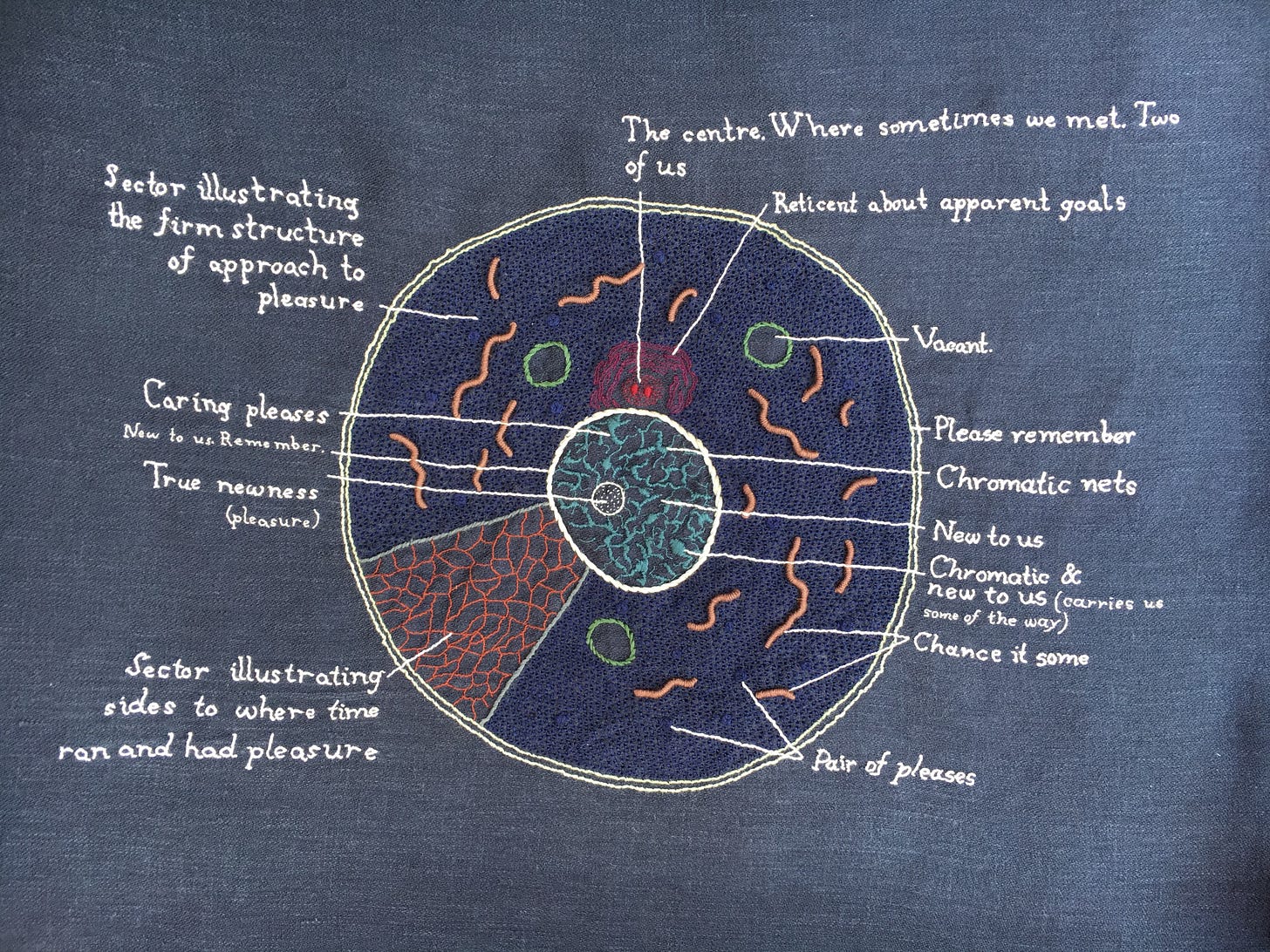

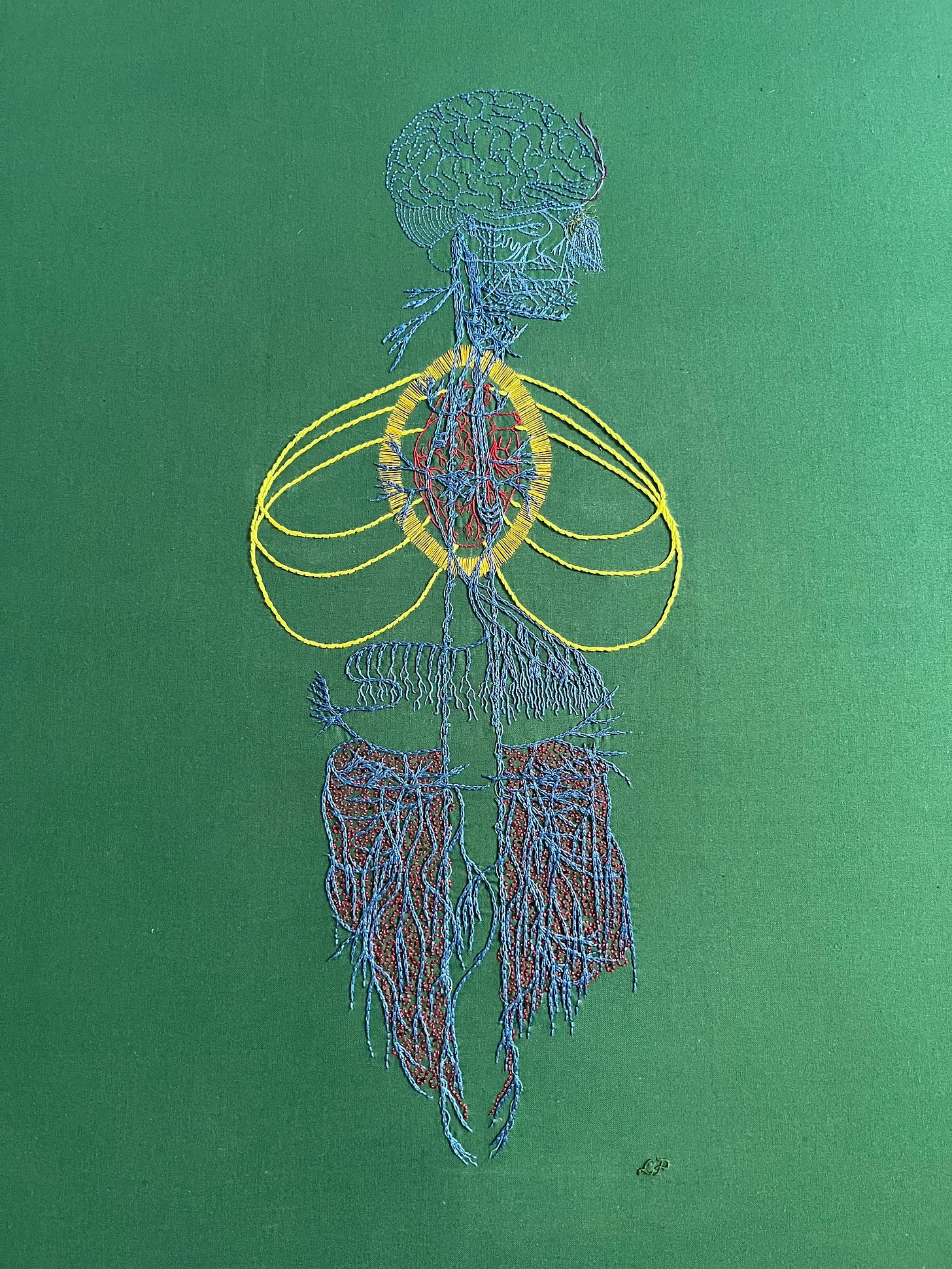

I've always been fascinated by science—my mom is a scientist and my dad did a geology degree—and have worked with scientific imagery in some of my performance and written work for many years. The microscopy series came out of some of my image/text work where I saw cell diagrams as maps and landscapes. The anatomy series shows my fascination with the beauty of human anatomy and how many of the shapes inside us are shapes found in nature. The symptomatology series combines my anatomy work and my meditation practice. When I'm symptomatic it helps to visualize what I am feeling and "dissect" those sensations to make them less overwhelming. Freehand stitching those sensations feels like a meditation practice as well. Sometimes these three series intermingle in ways that I don't anticipate during the creative process.

If you could show only one of the pieces to someone to help them understand you and your work, which one would you show and why?

Probably body map, since it gets across the symptomatology aspect of my work really well. It's one of my earlier pieces, but is very evocative of the overwhelming nature of ME/CFS. My work has gotten more anatomical since, but the symptomatology aspect is still a very important part of what I do.

Here it is:

I love this article you share on Meaning Making and would like to make sure people check it out. How would you describe/define the ways in which making and sharing this embroidery work makes meaning for you?

Since reading Eric Maisel's The Van Gogh Blues many years ago I've deeply understood just how imperative it is for me to make art of any sort. Making art is how I make sense of the world and of how I experience it. Without my creative practices I become irritable and depressed.

My embroidery work started as a way to do something creative that didn't overexert my body or cognition when I became ill with ME/CFS. The path of my science text/image into my symptomatology series shows how my meaning making has a throughline. I first saw the symptomatology series as intimate self-portraits, a way to understand the overwhelming symptoms I was having, to accept them as they occurred, and to find a sort of beauty in them. That process was natural meaning making for me. When I started sharing the work online I was surprised and moved by how much people related to the pieces. Many people have said the paresthesia pieces are accurate descriptions of what they feel as well. Others have said the more visceral anatomical pieces have helped them see their bodies as beautiful again, rather than as something to fight against. Seeing how what is intensely personal to me is also universal creates so much meaning, even beyond the sometimes scientifically educational aspect of my work.

That description of “intimate self-portraits” really stands out to me.

Can we discuss ME/CFS a little bit? What did you know about it before your diagnosis?

I had heard the term chronic fatigue syndrome before but had no idea what that really meant aside from being too tired to do things that most people did. ME/CFS is on a spectrum from severe (needing to be tube fed and completely bedbound) to mild (being able to work part time with proper pacing and supports). When I first got sick I was near the severe end of that spectrum, but thankfully I was able to eat daily and wash myself occasionally. I was very lucky that my GP has a friend with ME/CFS so she recognized the signs within a couple months and told me not to exert myself in any way. Radical rest near the beginning of my illness is likely part of why I'm now in the moderate to mild part of the spectrum.

What was your process of beginning to identify as having a disability?

There were two major instances that made it obvious to me that I was indeed disabled. The first was lending my electric piano to a friend because I wasn't using it at all. The fact that I couldn't sit up unsupported for more than a few minutes at a time paired with such severe hyperacusis I couldn't even listen to music on speakers was hard to accept at first because music had been my main creative practice since childhood. Seeing my piano leave the house made that loss very palpable. A few months later my friend found a used piano for her daughter and returned my electric one, and by then I was able to sit unsupported for longer and play for a few minutes at a time. I can play more now but I'm still very limited.

The second instance was buying a combined rollator/transport chair. Walking more than the length of my house without sitting down to rest results in post-exertional malaise (PEM), a type of neuro-immune exhaustion. This also made my disability very visible since a rollator is a fairly large mobility aid. After using it for a while I realized just how much it helped and how much more freedom I have with wheels. I've since upgraded to a lightweight foldable transport chair that I can lift on my own. My husband wheels me in when we're outside the house. Mobility aids = freedom so I encourage anyone who is on the fence about needing one to at least try one out because it's improved my life so much.

What are some of the most common misconceptions you've faced and how does your art work as a narrative to challenge them?

ME/CFS is very much an invisible illness on a couple different levels. We don't look sick, and most of us are housebound so hardly anyone sees us out in the community. Social gatherings are usually too much of an energy drain for us so we often can't attend them. I've had doctors in the ER tell me I don't look sick even when my symptoms and bloodwork show I have a serious liver infection from my Primary Schlerosing Cholangitis (PSC). We lose friends because they don't understand our limitations. My symptomatology series makes our many invisible symptoms visible. Illustrating my paresthesias/tingling seems to especially get the message across of just how overwhelming these symptoms can be.

I am always so disappointed to hear stories about medical professionals treating us that way.

Have you noticed any difference in the way people respond to ME/CFS since the COVID-19 pandemic and development of Long Covid?

There's been a little bit of a shift in awareness, but not as much as I would have hoped. More medical professionals seem to be aware of why I use a transport chair for fatigue so I don't have to explain that as often. I and many others with ME/CFS had hoped the world—and especially the healthcare profession—would take post-viral illnesses more seriously because of how prevalent they've become. But we're still dealing with misconceptions about masking in healthcare settings even during flu season and with the resurgence of measles. It's very frustrating to have to risk getting sick while seeking the care that we need.

What has it meant to you to have your work shown at medical humanities conferences, included on TED talks, and recognized outside of the fibre arts community?

Even before I started embroidering, some of my work was being shown in a medical humanities context, especially my videopoem susurrations and a few of my text/image pieces. There's a throughline from that work into my fibre arts pieces since I've long been obsessed with anatomy, especially historical anatomy art.

Even though the fibre art takes longer to create in some ways, the immediate visual impact of it seems stronger somehow, and I think that's what attracts people outside the fibre arts community too. I also feel like I'm doing good work when someone in the medical community interacts with my work. I try to be as scientifically accurate as possible while also taking a few artistic liberties to get sensations and symptoms across. That combination seems to give the work a more universal voice.

Here’s a TED Talk that shows Lia’s work:

You mentioned the experience of lending out your piano. What was the process like for you of letting go of musical performing and embracing embroidery?

When I first got sick, music was utterly impossible on so many levels so there wasn't even an element of choice there. I could listen to music on headphones but not on speakers because sound and vibration actually caused physical pain throughout my body. Speaking for too long exhausted me so singing was out of the question, as was sitting up at the piano. I had to let my voice students go, stop working on the dance opera I was in production with, and limit all aural inputs.

To be honest, I didn't even have the energy to mourn the loss of music at first. ME/CFS is not only physical and cognitive fatigue—strong emotions can also cause PEM. I spent a lot of time meditating and watching slow and ambient sci-fi, horror, and period dramas as well as playing a simple video game called Zen Koi. Reading nonfiction was almost impossible except in small doses, but I was able to read some fiction and to write for a few minutes at a time.

I knew from experience and reading The Van Gogh Blues that if I wasn't making meaning through some sort of creative practice I would get horribly depressed. I had dealt with depression in my 20s and 30s, and though the ME/CFS was utterly debilitating I knew I wasn't depressed because I wanted to do things. I was just too exhausted to do much of anything. In one of the period dramas I watched, a woman was told to "take to her bed and work on her embroidery" so I thought, why not? It would be something creative to do while lying on the couch for hours. My mom brought over the supplies from back when we did Ukrainian cross stitch and I drew out one of my scientific text/image pieces on cloth and went for it. It was slow yet engaging enough that I got hooked on it very quickly! I embroidered for many hours a day at first, but as my symptoms improved I added back some writing and music too.

I've always been a multidisciplinary artist, and I think my ability to switch between and integrate different creative practices paired with years of meditation coalesced into embroidery being a medium I could make meaning with.

You have described so well how you knew it wasn’t depression. As someone who lives with recurring depression myself, I know that it can be difficult to parse out the difference between it and various other physical and mental health conditions, so I think it’s helpful when people are able to do so.

What would you say was lost and what was gained in changing mediums?

I lost much of my physical community in the performing and writing world but I gained a new community online. I'm quite active on both the online SciArt and ME/CFS/chronic illness communities. I've been able to dip my toe back into music again via leaning into piano improvisation—traditional composing on paper has become very cognitively challenging but spontaneous composition still allows me to get into a flow state. I haven't found much music community because my piano-playing days are sporadic, though I have done some work with Opera Mariposa which is run by two sisters with ME/CFS.

One thing about having to pace myself so carefully is that I am utterly grateful for the times I am able to play music. I even get excited about scales and technique exercises in a way that I haven't before. I also have the gift of time to work on my various projects, though I usually have so many ongoing that prioritization is tricky. I used to have to go to a residency to get long stretches of time to focus on projects whereas now my studio days are very much like being at a residency. I alternate between deep work, general creative work, and practice/project days. I have very few meetings which saves my energy for the act of creativity itself.

I’m curious: what is similar and what is different about the mediums you’ve used?

There is a rhythm to embroidery that echoes the rhythms of music, especially when I'm working on a larger piece that has long lines of the same stitch. I've always been able to get into flow states quite easily, but because pacing myself is key I use timers for my more physically or cognitively active work. Within a couple minutes I can be in flow! I think my longtime meditation practice has definitely contributed to my ease of shifting states, but so has embroidery, especially when I am freehand stitching which is a type of improvisatory practice much like spontaneous composition.

I also find I am much more enamoured of process as opposed to focusing on finishing and presenting a piece. This explains why I have yet to frame any of my embroideries! I clean pieces up enough to get good photos of them but the work of framing them is a bit of a roadblock. Partially because it seems like it might be physically taxing—I may just hire someone eventually—but also because I would much rather spend my time making work.

One practice that has carried through since before I got sick is my writing, especially poetry. Letting go of the need to be cognitively lucid while writing poems has helped. I get aphasia—trouble finding the words for things—with my migraines but that can work in my favour in poetry since it can create interesting images and word pairings.

It sounds like you have found ways to be gentle with yourself, which has been one of the key things I’ve had to learn (and re-learn) as I’ve aged.

In what ways has your embroidery work changed from the time you started this fibre out to now?

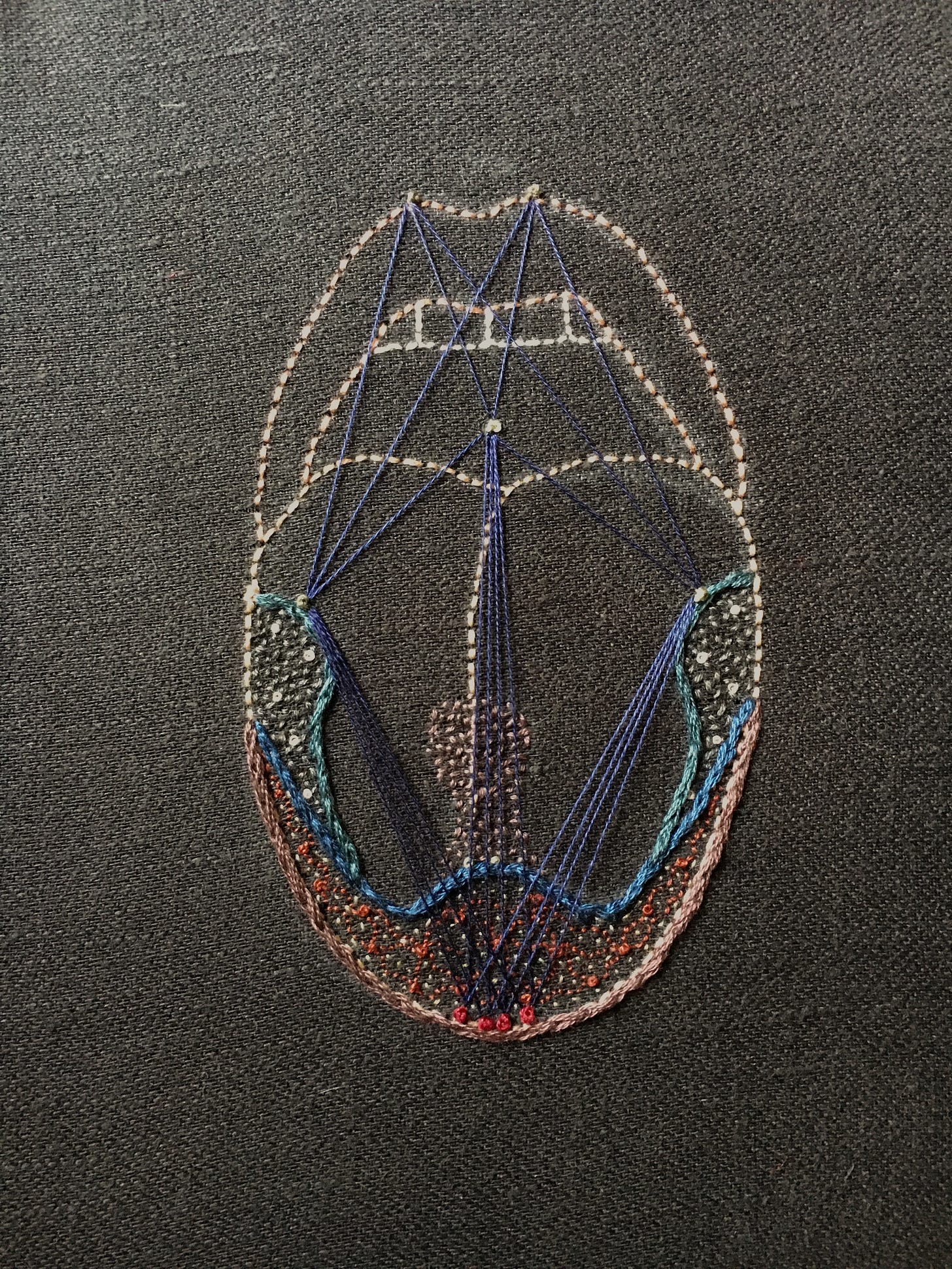

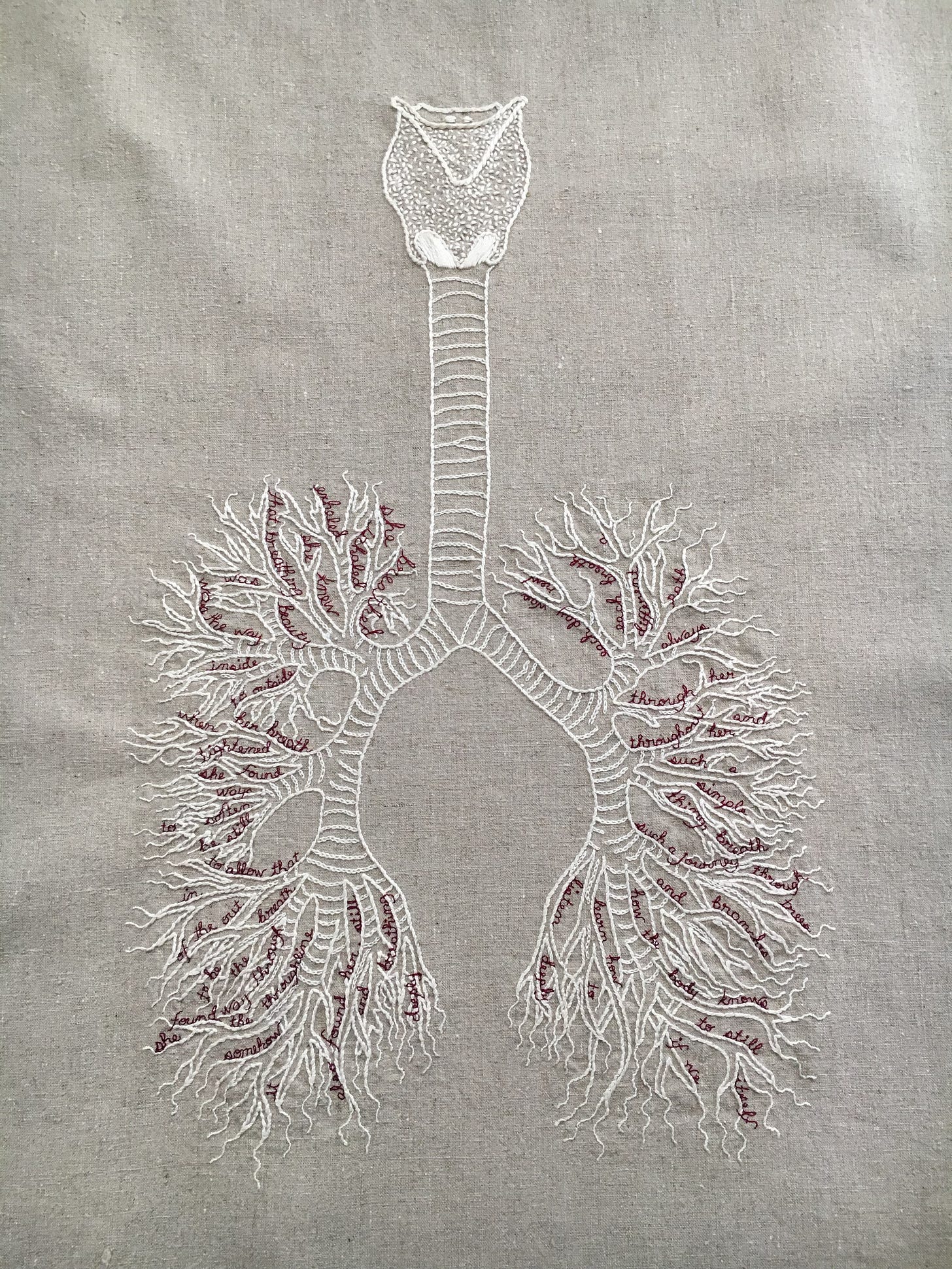

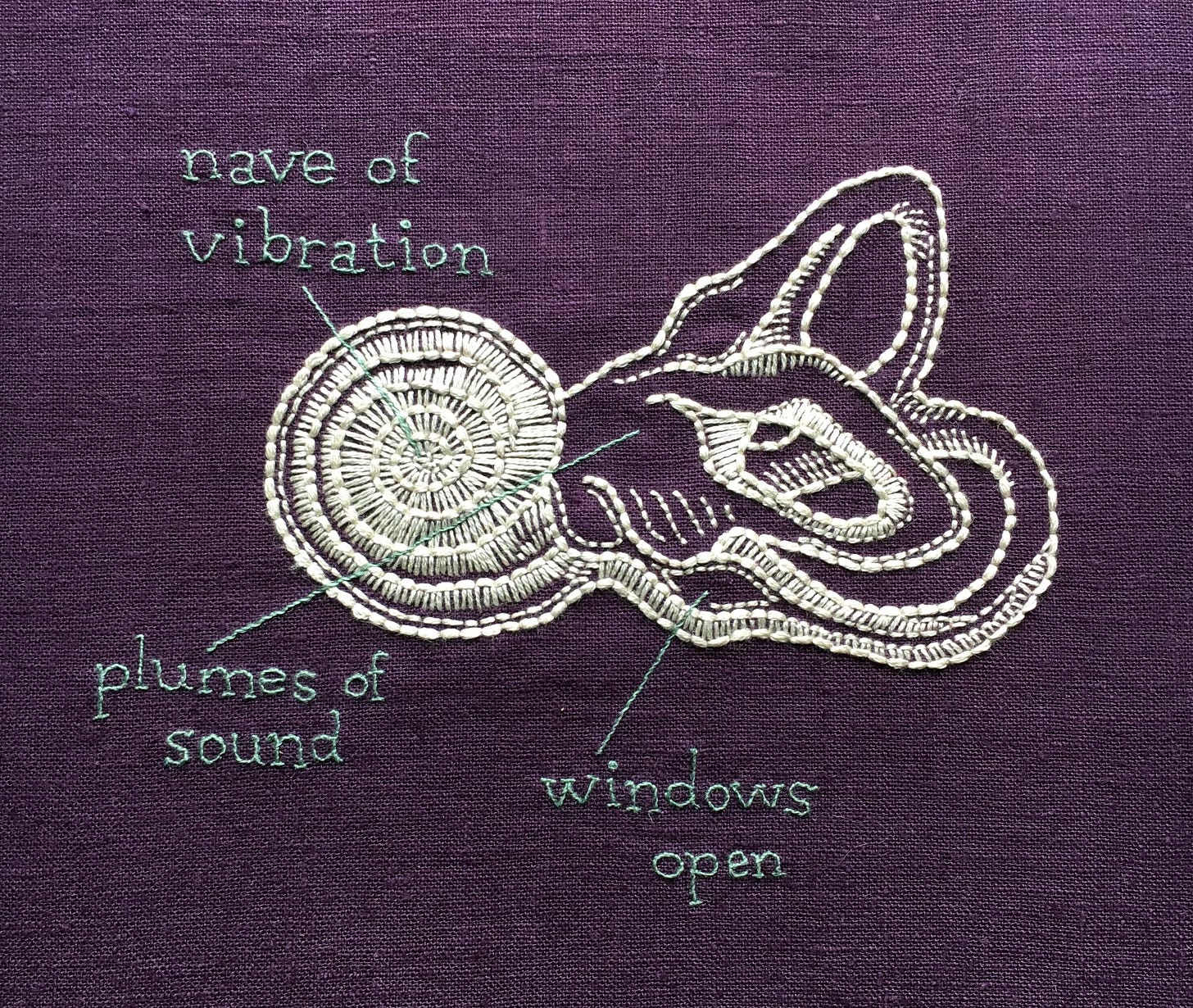

I started with anything sciencey—working from some poetic text/image collage work I had done before getting sick—and then was obsessed with my symptomatology series for a long while. I then returned to anatomy with pieces like she breathed and nave of vibration, and more recently have been combining both anatomy and symptomatology with some of my other illnesses like in tethered by fluid & ligaments and Bleeding Vessel.

Let’s look at those:

Read more about this piece:

I feel like I'm starting a new phase with the wandering ghost, exploring some metaphysical ideas on how the body/anatomy and the divine are intertwined. I'm working on a new piece right now that I'm being a bit secretive about because it may be the start of a new series. It explores the body, beauty, scars, and the Stoic concept of oikeiosis (interconnection with the cosmos).

Read more about this piece:

I've also gotten a lot more ambitious with my fibre art. My pieces are getting larger and I find myself learning new techniques to evoke the sensations I feel and the images in my mind. I learned a floating honeycomb stitch for a recent piece on my iliac vein stent which was a challenge but very worthwhile.

Be sure to check out all of Lia’s amazing work. In addition to what you can find on Substack, there are tons of links to images, audio, social media, poetry and prose here.